- The Wealthy Prognosis

- Posts

- Forever Young

Forever Young

Slowing down the wheel of time.

OUR ADDICTION TO GETTING OLD

Peter’s sister is convinced that he will outlive her despite him being 10 years older. Men also generally have lower life expectancies, averaging about 76 years old in the United States compared to 81 years for our female counterparts. Despite eating sour gummies by the handful, Peter has an otherwise impeccable routine that will ensure his longevity. As for myself, I’m hopeful for a similarly long and successful life.

For much of western medicine, people seek counsel from doctors and other healthcare professionals only when something has gone awry. This is no different when it comes to my clinical practice—people come seeking me out amidst the throes of life-changing events, dark depression, or florid psychosis. It is rare that a patient approaches my office seeking preventative counsel, though I am happy to see this trend slowly rising.

Our patients come to us when they are sick, and we partner with them on a journey in search for health. As such, I’ve long inquired about the steps to successful aging and how is it that some people, despite multitudes of medical ailments, continue to outperform even those who are objectively “healthier.” As a couple working in healthcare, we are intimately aware that being healthy encompasses many realms beyond just the physical. More and more research would suggest that achieving mental wellbeing translates directly into better outcomes for both physical and cognitive health.

When it comes to mental wellbeing, older adults face a variety of issues including mental illnesses, life satisfaction, and existential crises. Data from the World Health Organization and American Psychological Association suggest that a) 15% of people over 60 struggle with a mental illness, b) 6.6% of all disabilities in people over 60 are due to mental illness, c) 25% of deaths by suicide are in people over 60, and d) 7% of people over 60 struggle with depression compared to 5% in the general population. In addition to these staggering statistics, we also know that older adults tend to use more lethal means when attempting suicide (and thus are more often fatal) which is further exacerbated by issues of anxiety and insomnia (independent risk factors for suicide).

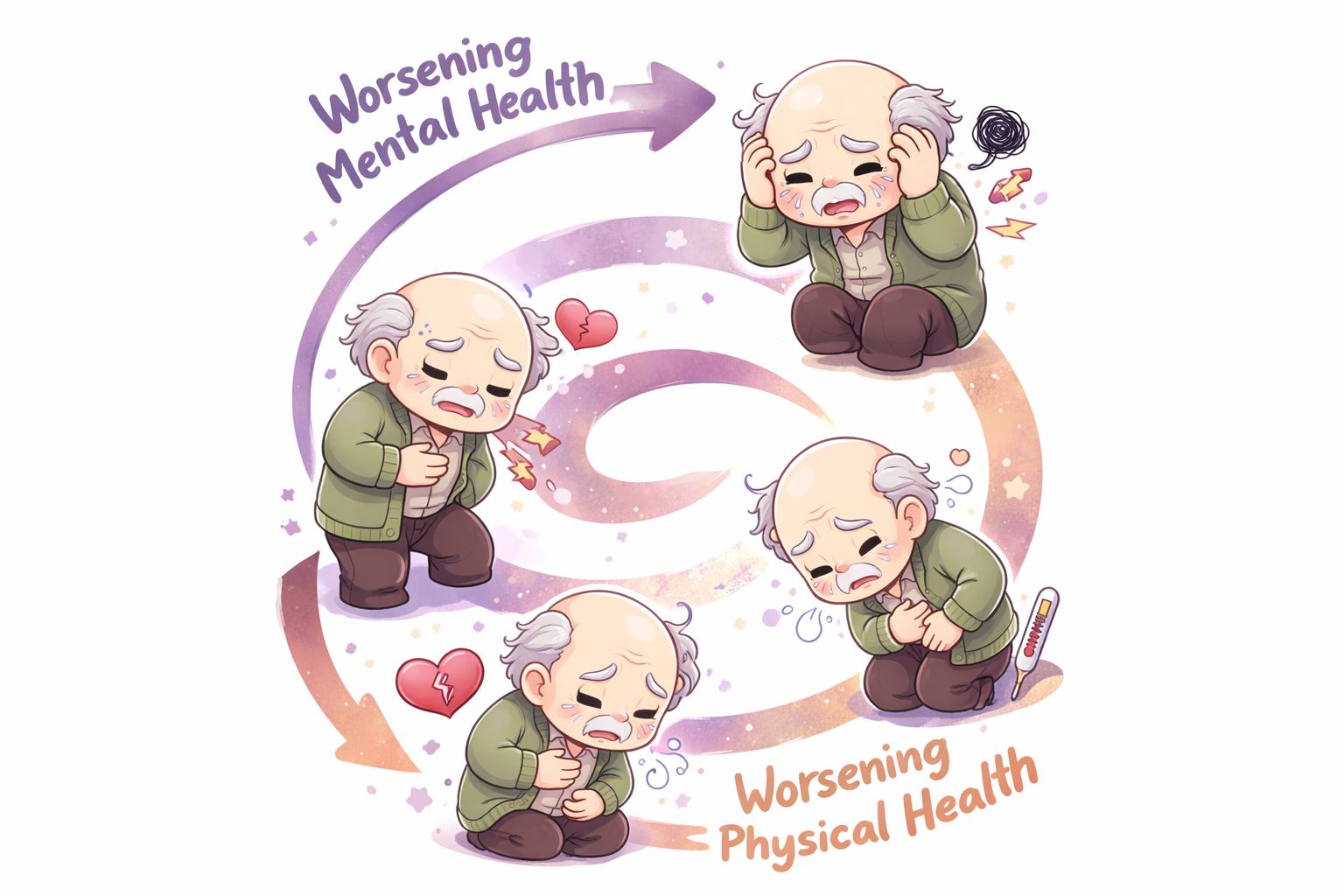

Beyond these numbers, we see that these factors are directly impactful to other spheres of health. Older adults struggling with mental health issues also face higher number and severity of co-morbid physical illness, reduced functioning, substance abuse, and personality rigidity (i.e., the inability to adapt and change). Interestingly (or not), mental health challenges not only increase risk of actual physical health limitations, but also increases one’s perception of poor health. This creates an insidious loop, often strongly positively reinforcing, which can make treatment of mental illnesses very challenging.

Louise Aronson, a geriatrician and writer from UCSF, said the following in her book, Elderhood: “At present, we count only a small fraction of medicine’s harms, prioritizing those suffered by patients over those to staff and systems, and counting almost exclusively the harms that visibly affect the body or its function while ignoring the scars of violent words, actions, and policies on psyches and relationships.” Though this quote brings to light an exquisitely sensitive subject within our healthcare system, I love that she pays full acknowledgement to the importance of our psyches and relationships as pillars of health. This quote also is inspiration for me and Peter to overcome the societal stigma of age: that somehow frailty defines the 6th decade of life and beyond.

There are discretely defined stages to aging which are not necessarily bound by specific ages: 1) independence, 2) interdependence, 3) dependency, 4) crisis management, and 5) end of life. The first stage is self-explanatory wherein older adults are able to take care of all activities of daily living—there are no limitations. There is minimal or no help needed in terms of caregiving. This is the stage that Peter and I look to extending and optimizing. In the stage of interdependency, there is some evidence of physical and/or cognitive limitations on the individual level, but partners are able to compensate for each other’s weaknesses.

Quality of life starts to decline here and the acknowledgement of one’s limitations (and inevitably requesting help) can make this a challenging stage. From stage 3 and beyond, there is a marked decline in quality of life as one is confronted with major losses in independence and mortality. Our goal is not only to prolong the stage of independence, but minimize the pain of the latter few stages.

We know there are several issues that come inherently with aging, namely a lost sense of purpose, financial insecurity, physical mobility, access to healthcare, and end of life preparations. Peter and I try to be conscious of our life decisions on both the micro and macro scales. Our monthly RADAR and yearly 8760 exercises forces us to re-examine our values, sources of fulfillment, and where to further derive or develop identity.

As we approach the fourth decade of life, some issues are more prescient than ever: issues around retirement and growing a nest egg for financial security when or if our bodies succumb to illness. Already, we find that our bodies do not recover as easily from physical activity and are more prone to injury. We are fortunate to work in the healthcare sector and thus have a good idea of how to navigate the complexity of the system here in the United States.

The idea of successful aging, however obvious it may sound, was not even a concept until the late 1980s or early 1990s. For decades, medical research focused on pathological versus “normal” aging, with little effort to understand truly successful aging. We know now that successful aging is characterized by freedom from disease and disability, high cognitive and physical functioning, and social and productive engagement. One of the seminal studies in this area is the Berlin Aging Study (1990-1993) which was a multidisciplinary investigation of over 500 people between ages 70-100. They found that increased spirituality and serenity (i.e., faith and acceptance) led to more successful aging. Though these individuals were often viewed as chronically ill in the eyes of their physicians, they often did not regard themselves as sick.

This pattern reflects some of the coping skills found in the elderly—humor and ability to compare themselves to those worse off (commonly understood as the practice of gratitude). Perhaps two of the strongest predictors of successful aging were high levels of education (demonstrating traits of self-care and “planfulness”) and extended family network (increased social engagement and support). Conversely, poor aging correlated with dependence, life dissatisfaction, and being bedridden. There is an ongoing Berlin Aging Study II which is longitudinally following a younger cohort to further assess the traits that aid in successful aging.

The biggest study in this area, however, comes from Harvard: the Study of Adult Development. This is a huge study involving hundreds of men who graduated Harvard in the 1940s along with men from inner city Boston. It’s an ongoing study that has been and continues to be headed by psychiatrists as it explores characteristics predictive of successful aging. Obvious involvement of things like career enjoyment, retirement experience, and marital quality were no brainers.

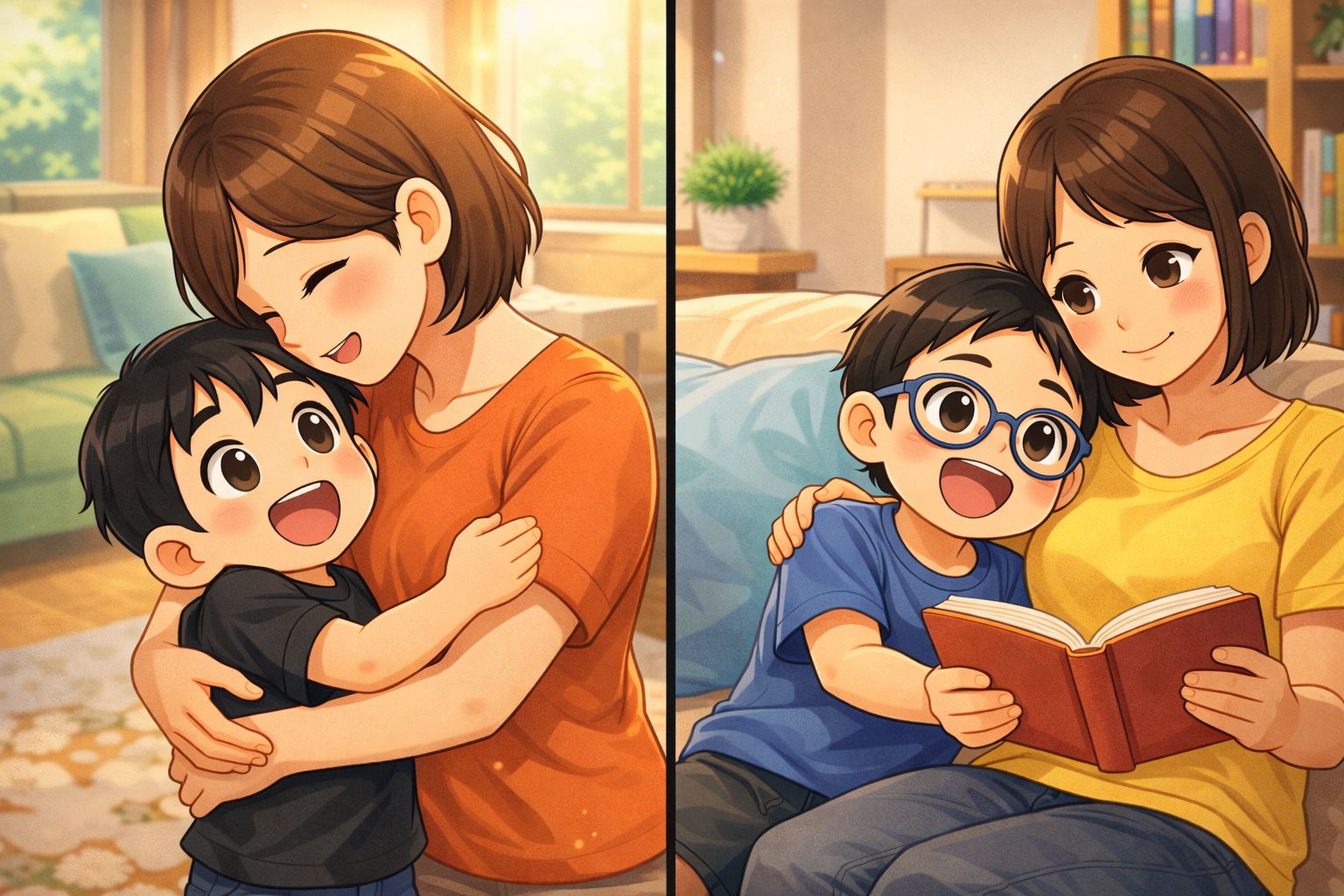

Less obvious were findings such as divorce being a predictor of worsened morbidity and death, political leaning being correlated with higher intimacy (liberal men tended to have active sex lives into their 80s whereas conservative men ceased around their late 60s), and warmth of childhood relationships. Warmer relationships with mothers predicted better financial success and reduced risk of dementia whereas warmer relationships with fathers predicted lower rates of anxiety. Dr. Robert Waldinger, the current director, has authored some really great books and even has a TED talk on this particular subject.

Poor Peter is subject to my ceaseless ramblings about this topic. He is more focused on the equally important matter of resilience. This has become central to much of our discussions as of late, especially as we figure out what to do with the rest of our lives. He has endured and overcome significant challenges in both his childhood and adulthood. Resilience is best defined as the ability to plan and prepare for, absorb, recover from, and adapt to adverse events. In essence, it is this quality that staves off the impending process of homeostenosis, or the ever declining physiologic reserve as we age. Higher levels of resilience are a direct correlate of better physical, mental, cognitive, and social functioning as one ages.

We used to think that resilience is a personality trait, but our understanding of it now is more aligned with it being a process. That is, people have the capacity to build and demonstrate resilience. This is done primarily through facing adversity through childhood and into adulthood. It is generated by those who seek continual self-development and opportunities to help others. In the Study of Adult Development mentioned above, it was found that achievement of midlife generativity produced a resilience effect in men, even as they endured heavy combat during World War II. Importantly, high levels of generativity and resilience counteracted the misfortunes of childhood adversity. This was positively associated with later life physical and psychological health.

In addition to resilience, good defense mechanisms or coping skills are key to living a long and happy life. Defense maturity is crucial in cultivating and maintaining social relationships. The Study of Adult Development found that men with immature defenses as young adults manifested increasing prevalence of chronic and irreversible health problems.

More adaptive defenses earlier in life predicted both objective and subjective physical functioning later in life (i.e., the feeling that they could do more). The underlying mechanism of this process is that better coping or defenses portended healthier social relationships: social involvement produced lower rates of mortality from cardiovascular disease, cancer, and infectious disease. In other words, loneliness kills!

If you’ve survived it this far into the article, we hope that you take away a few key points: 1) living well is a daunting task, 2) it is an undertaking that requires intentionality, 3) don’t sweat the small things and 4) invest in your relationships! Peter and I do the best with the hand we’re dealt, practice gratitude for the things we do have, maintain a healthy amount of optimism, and focus on building relationships both with ourselves and with others. In this way, we look forward to a good life, no matter how short or long.

XOXO,

Howard and Peter